From: g87

Sent: Thursday, January 31, 2013 2:37 PM

To: The Herald Sun

Subject: Scoop! Why Julia and 'Tim - bloke' are

childless!

Scoop! Why Julia and 'Tim - bloke' are

childless!

I guess Julia and Tim wisely decided to not have

children.

This way the concomitant lowering of our collective intelligence is not a problem: who said the lady does not have the country’s interest at heart?

However, she regularly manages disparate causus belli [even with her own disenfranchised Cabinet] and at least 4 catastrophes currently dominate the news, on the day she made the pathetic decision to launch the longest election campaign ever.

And all – along insisting she did not!

Asinity is not the word for the Labor brand.

There must be a new word to describe Labor - left AKA Gillard.

Geoff Seidner

East St Kilda

9RAW: Tim Mathieson's 'female Asian doctor' gaffe on MSN Video

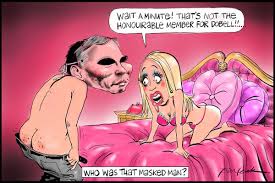

Great Bill Leak cartoon - Thompson,,months ago:

This way the concomitant lowering of our collective intelligence is not a problem: who said the lady does not have the country’s interest at heart?

However, she regularly manages disparate causus belli [even with her own disenfranchised Cabinet] and at least 4 catastrophes currently dominate the news, on the day she made the pathetic decision to launch the longest election campaign ever.

And all – along insisting she did not!

Asinity is not the word for the Labor brand.

There must be a new word to describe Labor - left AKA Gillard.

Geoff Seidner

East St Kilda

afr.com | Nova Peris

www.afr.com/tag/P_Nova%20Peris-KneeboneShare

7 days ago – PRINT: 29 January 2013 | PAGE 1 | In the face of

disasters ... Julia Gillard's

decision to parachute in Nova Peris

as Labor's next senator from ...9RAW: Tim Mathieson's 'female Asian doctor' gaffe on MSN Video

video.au.msn.com/...tim-mathieson...asian.../x7...Share

2 days ago

9RAW:

Tim Mathieson's 'female Asian doctor' gaffe

.....Description: This adorably dumb dog is having a

...News for latest news eddie obeid

-

Eddie Obeid to take the stand at corruption trial

ABC Online - 4 hours agoOne time New South Wales Upper House MP, Eddie Obeid, had a ...ANTONY GREEN: The last Labor government continues to be on the nose...

News for Thompson arrested

-

Craig Thomson arrested by police

NEWS.com.au - 9 minutes agoSUSPENDED Labor MP Craig Thomson is expected to be hit with 150 fraud charges after being arrested today, in a dramatic escalation of the.

Great Bill Leak cartoon - Thompson,,months ago:

Rubbish.

The "Old Nazis" were the New Islamists, whose sexually-deranged false prophet, Hitler but followed the old islamists sexually and in every other imaginable way, deranged false fuhrer, Muhummud.

Racism is rampant, and it will get worse.

No longer will people stand up to those Islamothugs, they have intimidated us.

Grobbbbbbbb

Now I would have pulled out the sweet little pistol with extended capacity and blown the muslims camel suckers back to alah…..

The Nazis were technically fascists.

Today's Fascist regime resides in the White House!

The idiots who voted him into office AGAIN are just as much to blame.

scum, rest assured the police would have been on him like ugly on ape and probably the Arab loving

Israeli High Court would have had him sentenced to life in prison....